I was told to come alone: my journey behind the lines of Jihad

by Souad Mekhennet (Virago, 2017)

This gripping tale of investigations across the Middle East is dramatic and authentic. It is based on 13 years of intense encounter with Jihadists and their supporters by a Muslim woman who is poised uneasily between worlds, working mostly for the principled Washington Post. The strength of Mekhennet’s personal but neutral engagement – she seeks, via face-to-face interviews, to learn why and how various individuals became Jihadists – gives great authority to her narrative-style reportage.

Though she is profoundly opposed to Jihadist murders and aims, Mekhennet writes with a sensitive German-Muslim insider’s feeling for what it is like to be an unwanted and alienated immigrant. She is further conflicted because her father is a Turkish Sunni and her mother a Moroccan Shia – and because she is a woman working in the male-dominated world of Western journalism, writing about Jihadist men who believe they are carrying out God’s will.

Mekhennet set off on this investigative journalist’s path because she took deeply to heart the cry from the mother of a murdered American who wanted to know, ‘why do they hate us?’ The whole book is essentially an enveloping answer to this question, taking us through hair-raising meetings with ISIS, al-Qaeda and other Islamists (plus the Egyptian and other security services) across Iraq, Algeria, Lebanon, Jordan, Pakistan, Egypt, Tunisia, Bahrain, Germany, France and Belgium, during 2003-2016. Along the way Mekhennet establishes an uneasy but enduring set of professional relationships with figures on the edge of the Islamist world, as well as a number of direct participants and some who direct and control the killers.

But what really sets this remarkable testimony apart is the personal history and integrity of the author herself, who gives a vivid picture of where and how she was brought up, in order, I think, to give full disclosure of just where she is coming from and how she is motivated. Mekhennet’s indomitable, demanding Moroccan grand-mother stands out as her guiding lodestar, though she only knew her as a small child when she was sent to live with her grandmother for a few years in a poor part of Moroccan city.

The book reads like a thriller, especially in the first half, as the journalist (who idolised Woodward and Bernstein, after seeing All the President’s Men) pushes herself against the odds – and at real risk to her life – into the frontline of Islamist terror reporting. She is very clear that Jihadists are led by false abusers of religion, completely unjustified in Islamic terms and also making the lot of Muslims worse, both inside their ‘caliphate’ and in the West. Equally, she is far from losing sight of the entrenched racism and prejudice in the West, along with the corrupt cruelty of despotic Arab regimes, which is what (she thinks) drives the Jihadists, along with their sense of powerlessness.

Treading this tightrope is not easy. About halfway through the book she writes: ‘I began to be deeply worried that the way I was trying to do my job – not taking any side but speaking to all sides and challenging them all whenever I could – was becoming untenable for someone with my background. Could this kind of impartial journalism about jihadists and the War on Terror be safely practised in the West only by someone whose parents were born and raised there, rather than someone whose Muslim descent made her an object of special interest and suspicion? … These … dark thoughts … made me question the foundations and ultimate success of the West’s supposed openness to outsiders and its commitment to freedom of speech and thought.’

This greater awareness raises Mekhennet’s memoir to the level of a serious and original contribution to Western political culture and self-examination. There is also much drama and even humour – such as when an Islamist leader proposes marriage to the author, only half-jokingly, at the very moment when she fears being kidnapped in the backstreets of a desperate Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. In the final chapter, we learn the affecting story of how the 16-year-old son of Mekhennet’s cousin (in Germany) is ‘brain-washed’ into joining Islamists in Syria, unfolding in real-time as Mekhennet tells it. There is a terribly fresh reality to the torment of the boy’s ‘normal’ parents, who fear their son’s death as well as his utter alienation from them, after a mere six months of becoming disaffected. ‘They’ are ‘us’.

Generally, the writer sticks to the docu-drama of what and who she encountered inside zones of terror (with detailed footnoting), and does not peddle her views or interpretations – indeed, she could perhaps have given us more analysis. However, in the last four pages Mekhennet does offer her overview of why ‘they hate us’: Western hypocrisy (with a series of invasive wars, extensive torture, drone killings, and pervasive prejudice against Muslims); the lack of dialogue within Islam about ‘what can and cannot be justified by our faith’; the feebleness of Imans and other Muslim leaders in not standing up clearly against intolerant and sexist Islamic practices; the fuelling of sectarian conflict and hence Jihadism by both Western governments and Middle Eastern leaders, for short term, blinkered ends; the ‘quiet war’ between Saudi Arabia and Iran; and the related shallow opportunism of those on all sides who seek easy answers and don’t bother to try to understand the ‘other’. She also mentions the broken homes and petty criminal backgrounds from which many Jihadists come, and the strong social bonds which they form with each other – but Mekhennet steers well clear of suggestions of widespread individual or social psychopathy, or any deep faults within Islam itself, as contributory causes.

She writes from a strong humanist and deeply practical viewpoint: ‘The world is not facing a clash of civilisation or cultures, but a clash between those who want to build bridges and those who would rather see the world in polarities.’ Her idealism is based on responding to the people caught in the middle: ‘If I’ve learned anything, it’s this: a mother’s screams over the body of her murdered child sound the same, no matter if she is black, brown or white; Muslim, Jewish, or Christian; Shia or Sunni.’

A minor note of criticism is that Mekhennet is ill-served by her book’s sensationalist title, while her supposedly greatest coup – unmasking the identity of the British-born Jihadist-John beheader – is the only dull part. Fortunately, the journalist’s understandable but trivial obsession with breaking a news story, rather than seeking a deeper understanding, is otherwise secondary.

Mark Hudson

Julho, 2017

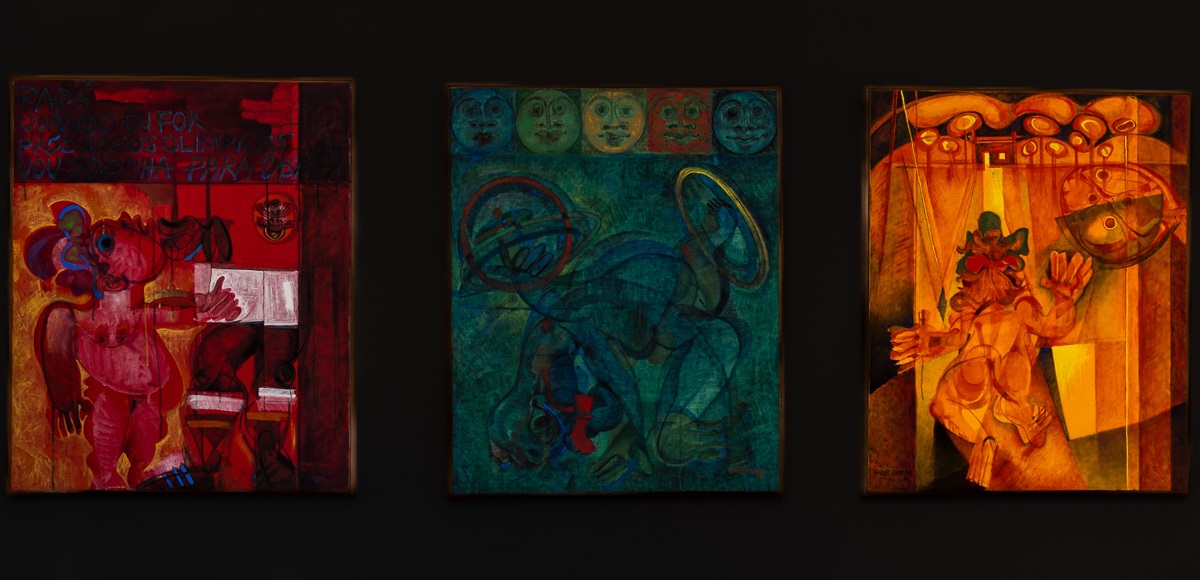

Fotos de Minnie Freudenthal e Manuel Rosário