Mr Five Per Cent, The many lives of Calouste Gulbenkian, the world’s richest man, by Jonathan Conlin (2019)

Masterly, under-stated hatchet job

First off, it has to be said that this scholarly biography has an irrelevant sub-title (‘the world’s richest man’), presumably intended to boost sales.

Having got that gripe out of the way, I must emphasise that this is a stupendous and readable work, based on an astonishing range of research, encompassing Turkish, Russian, Iranian, French and Portuguese archives, as well as British and American.

Besides a hostile work published by a relation in 1930 (regretting that Gulbenkian did so little for Armenians), a biography published in 1957 (two years after the death of its subject), and an out of print 2010 monograph by the Armenian Communities Department of the Gulbenkian Foundation in Lisbon, I cannot find another biography exclusively focused on this oil-finance and art-collecting magnate. (There is a two-part, imaginative historical novel based on Gulbenkian’s life, by José Rodrigues dos Santos, published in 2013.)

This is surprising, given Gulbenkian’s fecund ability to survive as an influential and independent player at the top end of global oil commerce for nigh on five decades, and through two world wars, both of which threatened his business with extinction.

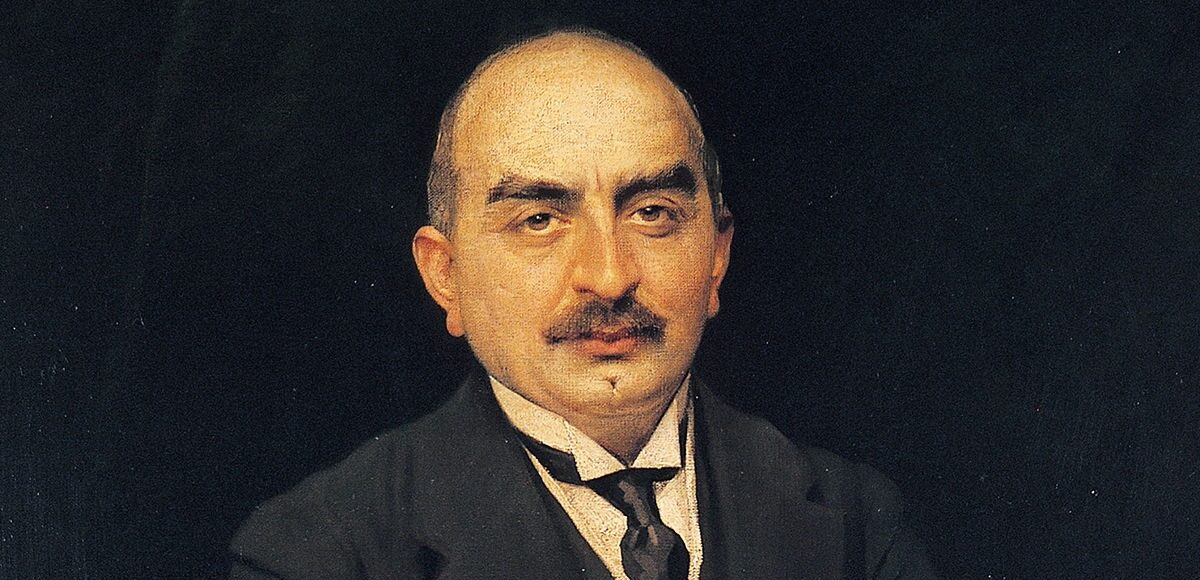

Calouste Gulbenkian (1869-1955) was a brilliant financial gadfly, a wheeler-dealer whose weakness was his greatest strength: he was not backed by any of the major powers – which at that time (1900 to 1950) were the USA, Britain, France and Russia/USSR – nor did he represent any of the major oil corporations.

He was the clever middleman between the prickly princes of the Middle East oilfields and the major Western oil companies. Gulbenkian understood the mindsets both of the ancient Ottoman ruling class and of the (largely) Anglo-American capitalists. This made him, if not an honest broker, then at least a respected recipient of confidences and concessions which enabled him to be a pivotal negotiator and semi-tolerated ringmaster for the huge economic forces of the emerging oil-producing world, in an age when personal contacts were still essential.

How did Gulbenkian do it? His undeviating focus on oil finance and his network of shifting alliances and informants, combined with his patient ability to manage the huge egos of the elite who ran the world, gave him a finger in every major oily pie. He knew which Ottomans to bribe; how to keep in with the powerful and eccentric chief of Shell; when to out-flank French ministers; how much to bribe the Armenian who drew up the infamous Sykes-Picot map in 1916 (to ensure that the best oilfields were in the British sphere); what the Shah of Iran would settle for; how to weave complex financial cross-holdings; and which Communist Russians he could deal with. He also knew how important it was to be highly secretive, and to stay in the background (unlike his son, Nubar), while maintaining a sufficient veneer of respectability and modest virtue. Gulbenkian was astute in not over-reaching himself, ensuring that the major oil corporations got the lion’s share of any deals in which he was involved, famously opining: ‘Better a small piece of a big pie, than a big piece of a small one.’

Conlin is fascinating – albeit too exhaustive for me – on the detail of Gulbenkian’s financial and business machinations. There are many revealing anecdotes, not least how he made his first millions via dubious dealings in South African goldfield shares, working in tandem with British speculators who were later charged with fraud.

Meanwhile, Calouste Gulbenkian’s family life was classically grim and controlling. At different times his wife, son and daughter tried to flee Gulbenkian’s gilded cage, but they lacked the strength of mind of their spidery captor.

Despite the claim in the sub-title (‘many lives’), the focus of this biography is overwhelmingly on oil finance. We are given disappointingly little on Gulbenkian’s art collection – and not much on how Portugal ended up with the bulk of his wealth, in the Gulbenkian Foundation. The story is told, but disjointedly.

Indeed, Portugal comes across as an accidental destination, relevant mainly as not being Britain, France or the USA – the far more likely destinations of Gulbenkian’s collection and his billions (especially the UK, where the art historian and director of the National Gallery, Kenneth Clark, had cultivated a long relationship with Gulbenkian). The Armenian tycoon did not want to be in the jurisdiction and hence in the power of a major player, which is why he stayed in Portugal (at the luxurious Avis Hotel), having fled France in 1942 when the Nazis abolished the Vichy government (Gulbenkian was the nominal economic adviser to the Persian legation at Vichy). For more than a decade after this, the unattractive and mildly sinister Portuguese dictator, Salazar, played a waiting game with the Armenian magnate, aware that billions were at stake. Salazar was aided – knowingly or not (this is not made clear) – by a clever Portuguese lawyer, Azeredo Perdigao, who had gained Gulbenkian’s trust.

After Gulbenkian was dead, he was quickly forgotten. Salazar packed the fledgling Board of the Gulbenkian Foundation with placemen and changed its focus to be overwhelmingly on Portugal, though Gulbenkian had stipulated – albeit not in the foundation’s trust deeds, as it was only constituted after his death – that only a maximum of 25% of the foundation’s income was to be spent in Portugal. (However, the Armenian had meant the foundation to be based in Portugal.) The Gulbenkian became a kind of private ministry of Portuguese culture, funded by the residue of Gulbenkian’s oil concessions, including 5% of the main Omani oil company. (Partex, the oil firm owned by the Foundation, was finally sold to a Thai company in June 2019.)

At the end of this impressively researched biography, one is left thinking, what was it all for? Did Gulbenkian matter? Yes, he played a significant financial part in the birth of the ‘seven sisters,’ the Western oil multinationals which dominated liquid carbon production during the twentieth century. So what?

As Conlin makes clear, Gulbenkian did little for his fellow Armenians, precisely at the time of their genocide by the Turks (see below); family life was wholly about loyalty to him, not love; he had no true friends; he had a voracious sexual appetite for young women (hence he always slept in hotels, not at home with his wife); he was interested in no causes (except, grudgingly, Armenia); and he was indifferent to the actual business of producing oil (only once visiting an oilfield). He was a master dealmaker, but not a strategist, as his only purpose was his own power and wealth, via inventing and hanging on to his 5%.

Nevertheless, and despite the vagueness of his intentions, Gulbenkian’s legacy to Portugal is considerable. His well-financed cultural foundation in Lisbon (with Euros 3.3 bn of assets at end 2019) is a major source of excellence and cultural life in the country. The vast majority of its annual expenditure (Euros 96 million in 2019) goes on activities and administrative salaries in Portugal. The museum’s art collection, based on the works bought by Gulbenkian (though much has been acquired since his death) is judicious and includes an eclectic range of truly fine pieces. Oddly, Gulbenkian rarely looked at the art he owned, and he never saw some of the works that he bought.

In keeping with the tradition for scholarly biographers not to take sides, Conlin does not advance his own opinion on Gulbenkian. He does not need to, as the facts – as he lays then out – speak for themselves. However, Conlin does make the unsubstantiated claim in the introduction that his subject’s life provides important lessons for the 21st century, without then explaining what these lessons might be. The only relevance I can see is that Gulbenkian added significantly to the reputation of financiers as callous, greedy and devious.

As a side-bar to Conlin’s book, it is interesting to compare the thoroughly credible story told by Conlin with that displayed in Gulbenkian’s entry in Wikipedia (in 2020). The latter is a white-wash job, portraying Gulbenkian as a significant philanthropist. In fact, during his lifetime he gave away little of his wealth, and his philanthropy was largely a matter of virtue-signalling (but perhaps that is typical of tycoons). Nor was he a ‘brilliant student’ at King’s College, London, as is claimed in Wikipedia, which also says that he obtained ‘a first class degree’. Conlin makes clear that, while undoubtedly gifted, Gulbenkian studied for a short term technical course, not a university degree, as the ambitious young Armenian was bursting to make money, not engineering calculations. Nothing is said in Wikipedia about the overwhelmingly unscrupulous (but well hidden) nature of Gulbenkian’s business dealings, where bribery was a major tool. There is no mention of his disregard for his family’s happiness or of his ruthless sexual conduct.

Perhaps most disingenuously, the (2020) Wikipedia entry claims that Gulbenkian ‘required that proceeds from his 5% of profits from oil should go to Armenian families,’ which is travesty of the truth. In fact, in his lifetime he gave what for him were small sums to relieve his suffering countrymen, and relatively little has trickled to Armenians since Gulbenkian’s death (the vast majority is spent in Portugal). The peak of the Armenian genocide by official Turkish forces – during which around 1 mn Armenians were murdered or died during forced marches in the Syrian desert – was during 1915-1923. This was precisely when Gulbenkian was most active in negotiating with the Turkish government for oil concessions and related business. (The blatantly fawning nature of the Wikipedia entry for Gulbenkian casts a blemish on the improved reputation for this generally wonderful, free human resource.)

Another curious footnote to the story of this highly intelligent but cold financier – who was probably not the richest man in the world by the 1950s, but number two, after his younger contemporary, John Paul Getty – is that his will was relatively unclear about who got what. This is surprising for someone whose whole life was devoted to making and keeping track of his money. Perhaps, Gulbenkian simply could not contemplate losing control: there was no deal he could cut with death.

Mark Hudson

Janeiro, 2021

Ver mais textos do autor

Britain remains in Europe

Brexit is about to happen. But Britain will remain inalienably part of Europe. The national myths, memories and mindsets of Britons, Portuguese, Greeks and Poles - and all those in between - are largely composed of the same sentiments. There are differences, chiefly historic and geographic, but these are massively

Jose Carneiro | 2021-01-25

|

Great Article ! Thanks Mark