There was, perched in the mountains that overlooked the valley of Vinales in the region of Pinar del Rio, a small pink house. In the house lived an old man with his wife and chickens and pictures of his long-departed children. Out front were two rocking chairs and a garden of roses. The valley lay before the house like a quilt, patchworked with plots of green and brown, and dotted here and there with neatly thatched tobacco barns. In the barns the leaves of the famous Havana cigars hung to dry.

Vinales is famous for its strange mountains. They are riddled with potholes and caves and underground streams, and thick jungle claws up their sides. There are ancient murals in them that were painted by the Indians who inhabited Cuba long before the Spanish came with their guns and slaves. Great chunks of these mountains stand abandoned, like monuments, on the valley floor.

Across the valley from the pink house was an elegant, pink hotel. It looked feudally down upon the peasants tilling their fields but was not filled with rich landowners and American gamblers as it would have been before the revolution, and now it was not even filled with foreign tourists. When I stopped there for a meal, it had a swimming-pool full of noisy school children and a restaurant where a scattering of middle-aged Cuban couples sat silently waiting for the one, unenthusiastic waiter to serve them.

I climbed into the mountains to the little pink house and was given a meal of cassava by the old man’s wife. When I left, the old man and his wife stood for a long while waving from their veranda and their dogs followed me until I was out of their jurisdiction. On the way down there was a thunderstorm. I huddled under the eaves of the remains of a barn and watched its passing through the valley. Around me red earth turned to red, dimpled water, dry gullies became roaring streams, smells of fresh grass and bark were borne on the sudden, chill wind, and the forests on the hillsides became glossy and pattered steadily like a thousand heartbeats.

My time in Cuba is full of such memories. Wherever I went on the island, from one end to the other, I met beauty and hospitality. There is the time, for example, when I could find nowhere to stay in the town of Baracoa…

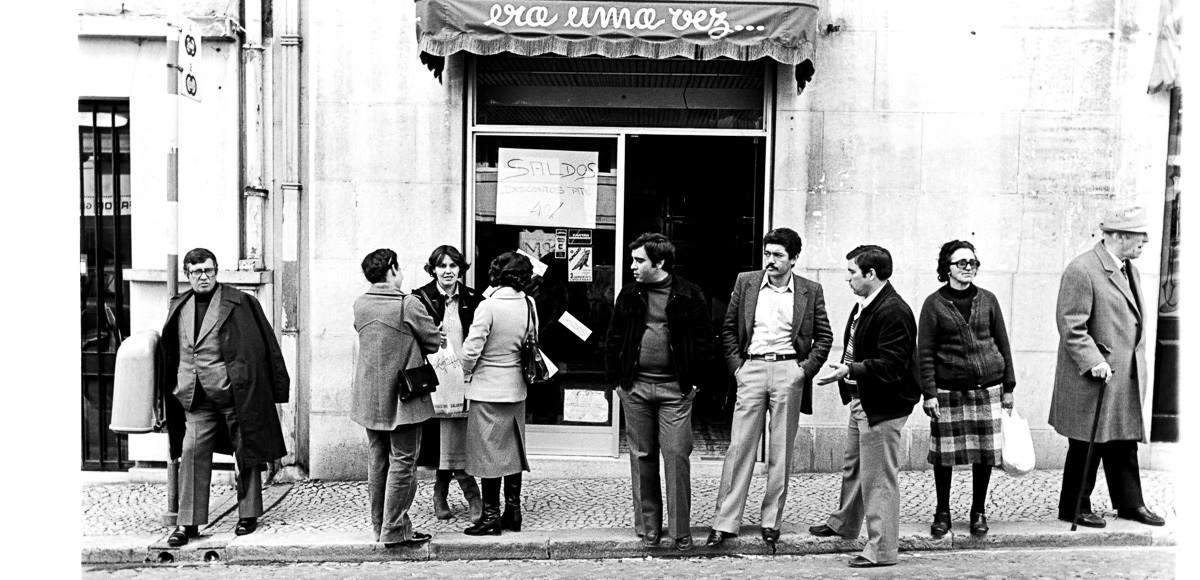

Baracoa is hemmed against the sea at the far, eastern end of the island by tall, wild mountains and was one of the first Spanish settlements in Cuba. It was a quiet town where not much happened because the hub of its life, fishing, had been nationalised. People rose late in the mornings and in the evenings sat in the town square watching the television set placed in front of a boarded-up cathedral, and they went to bed early. For some reason, the local hotels would not have me to stay. I was sitting on a doorstep wondering where I should sleep the night when a woman came up and gave me a cake. Then a young man invited me to his house. He was called Emilio, spoke English, and professed to be a pharmacist when in Baracoa and a pimp when in Havana. We drank cheap rum late into the night with his wife and old father. His wife was a Catholic and bewailed the state of religion in Cuba.

“They see my cross and my bible” she said, “and will not give me a job”. The old father reminisced about the days when the shanties of sack cloth and fish boxes littered with the bones of dogs which had been consumed for the evening meal had followed the railway lines and Rios far out of town; the days when the fishermen had had to work themselves to the bone in order to keep their families alive, but had had pride in themselves and their work.

Although it was illegal for foreigners to stay in people’s homes, I slept that night in Emilio’s bed whilst he slept with his father and his wife went to some neighbours, and in the morning, Emilio negotiated a place for me in a hotel.

There was the time I was befriended by a policeman in a remote beach resort on the far western tip of the island. The resort was for the use of Cubans, all of whom are entitled to two weeks paid holiday a year. The island is dotted with such places, but as the majority of Cubans take their holidays all at the same time, they have an abandoned atmosphere most of the year. Under tatty palms lines of mosquito-infested wooden shacks were strewn up the beach like the flotsam of a ship- wreck. A few perky dogs jogged along the surf, one or two couples sat listening to radios outside the shacks and that was about all. When night came and doused the place with dampness and solitude, a policeman found me wandering aimlessly around. He thought I must be lost because foreign tourists rarely left the up-market resorts laid aside for them and never came here, so he took me under his wing. We went to restaurant where he stirred the sleeping cook and had me eat a meal.

“Eat, eat” he said. “It will make you feel better”.

Then he took me to an empty bar where he watched me anxiously as I drank dark shots of rum. We kept each other company in this quiet corner of the world.

I had come to Cuba on an impulse. I wanted to see Fidel Castro’s haven of Communism at the heel of America. I wanted to see Ernest Hemingway’s ‘Island in the Stream’. I wanted to get involved in it, become steeped in its Spanish/African culture. When I first arrived, though, I found it an intractable and difficult place.

to be continued…

Peter Hudson,

1988

Fotos de Manuel Rosário e Minnie Freudenthal