Heriberto was my new friend’s name. He was a black Cuban from a poor suburb of Havana and had studied French at college, in which language a we communicated. He was youthful and earnest and, he said, always getting into trouble with the police about which, he told me, he did no care because he had nothing to lose

“I am a prisoner here in Cuba anyway”, he said. “What difference does it make if they put me in jail for a few days?”

Each evening we would meet on the Prado outside my hotel, then go wandering about the old town. Sometimes we would go to a bar called El Bodeguita del Medio. This was a place made famous by the fact that Ernest Hemingway had used to frequent it in his drinking, fishing and depressive period. Today its patrons were tourists and an odd selection of Cubans.

The bar was basic with a long, wooden counter, a stone floor and a couple of fans circling ineffectively overhead. In a corner behind a till on a tall stool sat the thin, watery-eyed manager who, it was said, had known Hemingway well. The walls of the place were covered in the silly, signatured phrases of past customers, some of whom had also been famous. ‘Mi daiquiri en El Floridita, Mi mojito en El Bodeguita,’ Hemmingway had written.

The glasses for the mojitos lined the length of the bar. First in went the ice, then a squeeze of lime, then mint and sugar, and then, with a loose and generous hand, the rum topped up with soda. A quick stir and the glasses would disappear to be replaced moments later by a fresh consignment. The cool, refreshing result slipped down well in the heat, and when later you walked around the corner to the beautiful, stone-clad Plaza de la Catedral you’d feel imbued with a sense of well-being, and content to sit for many an hour on the cathedral steps listening to the echoing, dark-mouthed alleyways.

Heriberto would drink short dark rums on a stool at the bar whilst I drank the mojitos. There was an atmosphere of bohemianism in the place. Here, one felt, politics could be discussed, and in Cuba conversations very quickly turned to politics.

“If you become a good party member, are an opportunist, then you can get anywhere in Cuba. Do as you are told and the government will provide: water, health, housing and education; we have it all. But people cannot fulfil their potential. Young people are frustrated, bored. Their youth is castrated” and so on. The surface needed only the slightest scratch to discover the anger and resentment in Cuba.

Charles, we met one night in a dark bar off the Prado. He was an African from the Ivory Coast, the son, he told us, of an ex-finance minister. He was on a tour of Communist countries and Cuba was his first. “Communism”, he said as he drank his rum and eyed the passing girls, “is good, very good.”

He was with Tani, and they had two girls with them, seated in their laps. We sat in the bar with them until one of the girls had a row with a waiter, and we were asked to leave. Out in the street it was quiet and hot. We hailed a taxi, one of the 1930’s Chevrolets that always seem to be driven by men who hailed from much the same era as their vehicles, and went to the Habana Libre, a grand modern hotel, the show-piece of the New Town. Here the girls had a whale of a time ordering a relay of the most expensive drinks until here too they had an argument.

“We said three daiquiris, not two, you idiot.”

Tani told them to drink what they had and we left.

Tani had been, or still was, a dancer. He was tall and handsome and had a way of walking with his head thrown back and his arms hanging loosely at his sides that seemed to announce that he was a dancer.

“A true Cuban, a truly good Cuban”,Charles would say of him, slapping him on the back. It was he, Tani, who suggested that we rent a house on the beach. It would be cheap, he said, and we could have a great party.

The house we took was situated in an area of holiday apartments for Cubans and was small and basic. The beach was only a couple of minutes’ walk away. In the mornings I would go for a swim, and sometimes Tani and Charles would accompany me. Neither of them knew how to swim, however, though neither of them would admit this. Then one day I saw Tani jump into a swimming pool in what he must have though was the shallow end but in fact turned out to be the deep one. Down he went, the water closing over his head, and up he came, wide-eyed and spluttering.

“I am a dancer”, he said, once safely out of the pool, “what use do I have for water?” So instead of swimming he lay on the beach harassing pretty girls.

The woman who rented the house to us lived on the top floor. She was a large, motherly figure who seemed always to be washing clothes and would come down to our patio in the mornings to chat with us and bring us coffee, because we never had any. It was illegal for her to rent her house to a foreigner but she did not care. Heriberto said that it was her way of showing her contempt for the Communists. Tani had picked up a two of girls who did our washing and cooking, smoked all our cigarettes, drank our beer and sat in our laps. They sloped around the place oozing sensuality, and each night there was an ordeal as Heriberto and Tani tried negotiating them into bed.

Because the place we were in was a holiday area, there were clubs and cabarets to go to every evening. Tani had a favourite one near to the house to which we went a number of times. The first time the place was virtually deserted. Whether the clubs were full, however, which more generally they were, or empty, the cabaret would always go ahead with full vitality. Also, regardless of whether they were empty or not, there would always be a long delay at the door. There were always long delays at doors in Cuba.

There would be a band and singers and poets, and then the ‘Extravaganza’. Tall, slim girls in dazzling costumes of gold and plumes showing plenty of naked flesh would stream in, dancing and writhing with sinuous men gyrating about them. Then an older woman, the Queen of the show, in a long tight-fitting dress would swager out and sing ‘la pièce de la pièce’ and the audience would be up on their feet singing along and clapping, their eyes rivetted to the swaying hips of the girls.

‘Ah, look at that one, she is for me. I shall invite her for drink. She is so bea..u…tiful, so bea..u..tiful,’ Tani would be crying in his frenzy of dancing and drinking. Then the ‘Extravaganza’ would finish with a flashing explosion and smoke and the Queen would give a low bow revealing her ample cleavage and wave and then everybody would be up on the stage with the girls, dancing, twirling their partners, their hips moving in time to the music as though they had a life of their own. They’d dance until the sweat poured off them and the song ended, and then they’d come back to their tables and drink neat rum because by now the bar would be out of Coke and ice with which to mix it. Then soon the band would strike up the next number and they’d all be up again.

to be continued…

Peter Hudson

1988

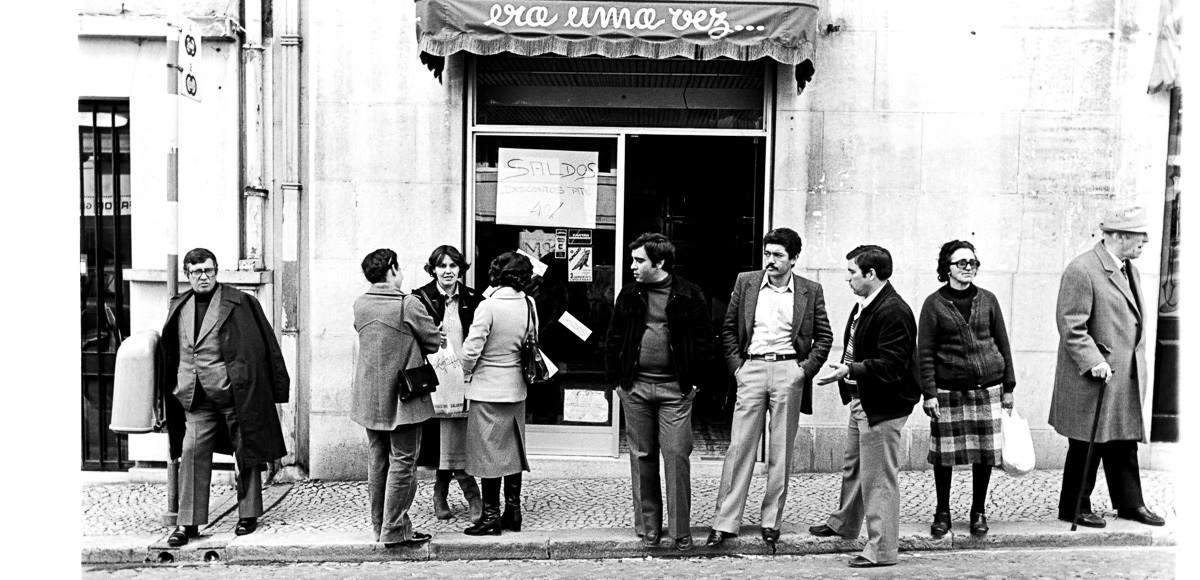

Fotos de Manuel Rosário e Minnie Freudenthal