There is no place in Macau dearer to me than Largo do Lilau (“square of granny’s well” in Chinese), for the sole reason that I grew up there. It was where I used to play and run about, learned to ride first a tricycle and then a bicycle. I only discovered much later that it was a huge privilege to have grown up there, not only because it was, and still is, a beautiful place, but also because it is a place of great relevance for both the Chinese and the Macanese (whose identity references are Portuguese) communities. It is the heart of an important heritage site that has been left relatively undamaged by the ruthless real estate sector, although up to a certain point one could argue that the territory is so tiny that in order to build one has to destroy to make room.

The square is surrounded by houses built in the “Portuguese” style, which used to be the residences of the most prestigious Macanese families in the past. However, what makes it so fascinating to me today is that it is a place where the Chinese and Macanese communities really lived, and still do, side by side. From my house, the ground floor of a modest two-storey house on the less posh side of the street, I could see my Macanese neighbours’ dining room where they received the priest’s visit every week. Here I must add that in Macau, the different communities used to live in distinct areas. Lilau definitely was once a chic Macanese residential area and has gradually been infiltrated by people of more humble origin. Nevertheless, the presence of the Mandarin’s house in the area suggests that the Chinese infiltration began with the privileged upper classes as well.

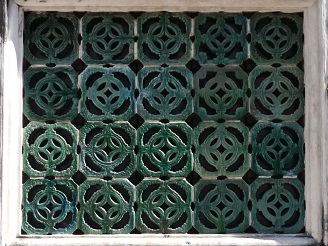

The Portuguese designation “Casa do Mandarim” indicates the social position of its original owner, whereas its Chinese designation “Zheng’s Mansion” gives us his family name. This huge compound (some 4000m²) was built in 1881 by Zheng Wenrui, an honorary mandarin, although it is his son, Zheng Guanying, who is remembered for his philanthropic deeds and modernist ideas as well as his personal friendship with the activists of the reform movement, which included Sun Yat-sen, the founding president of the First Republic of China. By the time I was born, this piece of fine Chinese architecture had been reduced to a ruin of divided ownership, occupied legally and illegally by hundreds of tenants, sub-tenants, squatters and even factories, and regularly ravaged by fires. The kitchen window of my house faced its main entrance. Even as a child I could tell that its occupants belonged to a very low social stratum. It was also not difficult to understand that there were illicit activities going on inside, such as clandestine gambling, for every so often there would be a raid and I would see my neighbours being hauled away in cage-like cars. The place was a real hotchpotch of people: policemen, prostitutes, gamblers and people from all walks of life cohabiting within its confines.

In the middle of the square there were three, now only two, gigantic banyan trees in a row, their shade providing a haven to two food stalls that were separated by the central tree. One stall was owned by a Chinese brother and sister, and the other by a Macanese widow with a powerful voice. They served pretty much the same things: tea, coffee, sandwiches and quick noodles, but the clientele was completely different. My grandmother, like many others of her older Chinese neighbours, would have breakfast at the Chinese stall and chat her mornings away. The Macanese in the neighbourhood, at that time mostly lower-ranking civil servants who were allocated part of one of those grand houses to live in by the government, would have breakfast at the widow’s stall instead. The few remaining “aristocrats” in the square seldom took part in this street life. There was a strong internal class barrier within each community. Only children, among them myself and my playmates from both communities, would disregard this divide and cross the invisible boundary, announcing and contributing to the process of ethnic approximation, at least along the social class line.

P.S.

Fast forward almost 50 years, it is quite ironic that it is I who now live in Portugal, the referential patria of my Macanese playmates, speaking now the language that they used to tease me with, while their children are learning to read and write Chinese instead of only speaking it, and marrying Chinese people. One can say a real ethnic approximation has happened. Whatever hostility existed between the two communities and despite my Macanese neighbours’ unmindful betrayal of superiority they were my best childhood friends, and I always think of them with tender feelings and great gratitude, for having allowed me into their intimate space, for showing me how to cook those delicious fusion Macanese dishes and sharing them with me. And finally, at this time of my life, I have to acknowledge that after all it was not by chance that I ended up here in Portugal, there is a much larger historical causality factor in my apparently personal trajectory.

Monica Chan

Outubro, 2017

Fotos de Monica Chan